这个理论很有趣的一点是:人们对金钱上的收入和损失的心里感受是完全不平均的。当你得到一点点的时候,你满足感会上升的很快,以至于你持续得到很多钱以后,你的满足感反而上升的变慢了;当你失去一点钱的时候,你很痛苦,但是随着你失去的越来越多,你反而不会像以前那么痛苦了。

[separator]

Model

Prospect theory was developed by Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky in 1979 as a psychologically realistic alternative to expected utility theory. It allows one to describe how people make choices in situations where they have to decide between alternatives that involve risk, e.g. in financial decisions. Starting from empirical evidence, the theory describes how individuals evaluate potential losses and gains. In the original formulation the term prospect referred to a lottery.

The theory describes such decision processes as consisting of two stages, editing and evaluation. In the first, possible outcomes of the decision are ordered following some heuristic. In particular, people decide which outcomes they see as basically identical and they set a reference point and consider lower outcomes as losses and larger as gains. In the following evaluation phase, people behave as if they would compute a value ( utility), based on the potential outcomes and their respective probabilities, and then choose the alternative having a higher utility.

The formula that Kahneman and Tversky assume for the evaluation phase is (in its simplest form) given by

where

where

are the potential outcomes and

are the potential outcomes and

their respective probabilities.

v is a so-called value function that assigns a value to an outcome. The value function (sketched in the Figure) which passes through the reference point is s-shaped and, as its asymmetry implies, given the same variation in absolute value, there is a bigger impact of losses than of gains (

loss aversion). In contrast to Expected Utility Theory, it measures losses and gains, but not absolute wealth. The function

w is called a probability weighting function and expresses that people tend to overreact to small probability events, but underreact to medium and large probabilities.

their respective probabilities.

v is a so-called value function that assigns a value to an outcome. The value function (sketched in the Figure) which passes through the reference point is s-shaped and, as its asymmetry implies, given the same variation in absolute value, there is a bigger impact of losses than of gains (

loss aversion). In contrast to Expected Utility Theory, it measures losses and gains, but not absolute wealth. The function

w is called a probability weighting function and expresses that people tend to overreact to small probability events, but underreact to medium and large probabilities.

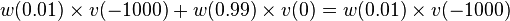

To see how Prospect Theory (PT) can be applied in an example, consider a decision about buying an insurance policy. Let us assume the probability of the insured risk is 1%, the potential loss is $1000 and the premium is $15. If we apply PT, we first need to set a reference point. This could be, e.g., the current wealth, or the worst case (losing $1000). If we set the frame to the current wealth, the decision would be to either pay $15 for sure (which gives the PT-utility of

v( − 15)) or a lottery with outcomes $0 (probability 99%) or $-1000 (probability 1%) which yields the PT-utility of

. These expressions can be computed numerically. For typical value and weighting functions, the former expression could be larger due to the convexity of

v in losses, and hence the insurance looks unattractive. If we set the frame to $-1000, both alternatives are set in gains. The concavity of the value function in gains can then lead to a preference for buying the insurance.

. These expressions can be computed numerically. For typical value and weighting functions, the former expression could be larger due to the convexity of

v in losses, and hence the insurance looks unattractive. If we set the frame to $-1000, both alternatives are set in gains. The concavity of the value function in gains can then lead to a preference for buying the insurance.

We see in this example that a strong overweighting of small probabilities can also undo the effect of the convexity of v in losses: the potential outcome of losing $1000 is overweighted.

The interplay of overweighting of small probabilities and concavity-convexity of the value function leads to the so-called four-fold pattern of risk attitudes: risk-averse behavior in gains involving moderate probabilities and of small probability losses; risk-seeking behavior in losses involving moderate probabilities and of small probability gains. This is an explanation for the fact that people, e.g., simultaneously buy lottery tickets and insurances, but still invest money conservatively.

[ edit] Applications

Some behaviors observed in economics, like the disposition effect or the reversing of risk aversion/ risk seeking in case of gains or losses (termed the reflection effect), can also be explained referring to the prospect theory.

An important implication of prospect theory is that the way economic agents subjectively frame an outcome or transaction in their mind affects the utility they expect or receive. This aspect has been widely used in behavioral economics and mental accounting. Framing and prospect theory has been applied to a diverse range of situations which appear inconsistent with standard economic rationality; the equity premium puzzle, the status quo bias, various gambling and betting puzzles, intertemporal consumption and the endowment effect.

Another possible implication for economics is that utility might be reference based, in contrast with additive utility functions underlying much of neo-classical economics. This means people consider not only the value they receive, but also the value received by others. This hypothesis is consistent with psychological research into happiness, which finds subjective measures of wellbeing are relatively stable over time, even in the face of large increases in the standard of living (Easterlin, 1974; Frank, 1997).

Military historian John A. Lynn argues that prospect theory provides an intriguing if not completely verifiable framework of analysis for understanding Louis XIV's foreign policy nearer to the end of his reign. As he briefly explains the theory, it "argues that individuals choose actions or objects not simply by rationally weighing their intrinsic utility. The theory states this by arguing that people measure utility by some variable reference point, not by some immutable scale. . . Tests show that people place higher value on things that they already regard as their own than on comparable things that they do not possess." Applied to Louis XIV's foreign policy, it promises to explain his actions that helped lead to the Nine Years War and the War of the Spanish Succession. Lynn elaborates, asserting that "[a]ccording to prospect theory, it would be entirely reasonable for Louis to invest great effort and accept high risk in the name of defending his old territories and new acquisitions. Here extreme behavior would be the natural product of a defensive mentality and not of an acquisitive drive." (Lynn, pp. 43-44)

[ edit] Limits and extensions

The original version of prospect theory gave rise to violations of first-order stochastic dominance. That is, one prospect might be preferred to another even if it yielded a worse outcome with probability one. The editing phase overcame this problem, but at the cost of introducing intransitivity in preferences. A revised version, called cumulative prospect theory overcame this problem by using a probability weighting function derived from Rank-dependent expected utility theory. Cumulative prospect theory can also be used for infinitely many or even continuous outcomes (e.g. if the outcome can be any real number).

Recently, scholars have connected prospect theory to optimal foraging theory, noting that survival thresholds might be responsible for the origin of prospect theory preferences in humans (McDermott et al. 2008).

[ edit] Sources

- Easterlin, Richard A. (1974) "Does Economic Growth Improve the Human Lot?" in Paul A. David and Melvin W. Reder, eds., Nations and Households in Economic Growth: Essays in Honor of Moses Abramovitz, New York: Academic Press, Inc.

- Frank, Robert H. (1997) "The Frame of Reference as a Public Good", The Economic Journal 107 (November), 1832-1847.

- Kahneman, Daniel, and Amos Tversky (1979) "Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk", Econometrica, XLVII (1979), 263-291.

- Lynn, John A. (1999) The Wars of Louis XIV 1667-1714. United Kingdom: Pearson Education Ltd.

- McDermott, Rose, James H. Fowler, and Oleg Smirnov. "On the Evolutionary Origin of Prospect Theory Preferences." Journal of Politics, forthcoming (April 2008) Paper Available at SSRN: http://www.ssrn.com/abstract=1008034

- Post, Thierry, Van den Assem, Martijn J., Baltussen, Guido and Thaler, Richard H., "Deal or No Deal? Decision Making Under Risk in a Large-Payoff Game Show" (April 2006). EFA 2006 Zurich Meetings Paper Available at SSRN: http://www.ssrn.com/abstract=636508

- http://prospect-theory.behaviouralfinance.net/