Bayes' theorem

- 2008-04-28 22:40:15

- mlzy

- 原创 13602

In probability theory, Bayes' theorem (often called Bayes' Law) relates the conditional and marginal probabilities of two random events. It is often used to compute posterior probabilities given observations. For example, a patient may be observed to have certain symptoms. Bayes' theorem can be used to compute the probability that a proposed diagnosis is correct, given that observation. (See example 2)

As a formal theorem, Bayes' theorem is valid in all interpretations of probability. However, it plays a central role in the debate around the foundations of statistics: frequentist and Bayesian interpretations disagree about the ways in which probabilities should be assigned in applications. Frequentists assign probabilities to random events according to their frequencies of occurrence or to subsets of populations as proportions of the whole, while Bayesians describe probabilities in terms of beliefs and degrees of uncertainty. The articles on Bayesian probability and frequentist probability discuss these debates at greater length.

[separator]Statement of Bayes' theorem

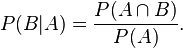

Bayes' theorem relates the conditional and marginal probabilities of events A and B, where B has a non-vanishing probability:

Each term in Bayes' theorem has a conventional name:

- P( A) is the prior probability or marginal probability of A. It is "prior" in the sense that it does not take into account any information about B.

- P( A| B) is the conditional probability of A, given B. It is also called the posterior probability because it is derived from or depends upon the specified value of B.

- P( B| A) is the conditional probability of B given A.

- P( B) is the prior or marginal probability of B, and acts as a normalizing constant.

Intuitively, Bayes' theorem in this form describes the way in which one's beliefs about observing 'A' are updated by having observed 'B'.

[ edit] Bayes' theorem in terms of likelihood

Bayes' theorem can also be interpreted in terms of likelihood:

Here

L(

A|

b) is the likelihood of

A given fixed

b. The rule is then an immediate consequence of the relationship

.

.

With this terminology, the theorem may be paraphrased as

(where α is a normalising constant).

In words: the posterior probability is proportional to the product of the prior probability and the likelihood.

[ edit] Derivation from conditional probabilities

To derive the theorem, we start from the definition of conditional probability. The probability of event A given event B is

Equivalently, the probability of event B given event A is

Rearranging and combining these two equations, we find

This lemma is sometimes called the product rule for probabilities. Dividing both sides by P( B), providing that it is non-zero, we obtain Bayes' theorem:

[ edit] Alternative forms of Bayes' theorem

Bayes' theorem is often embellished by noting that

where A C is the complementary event of A (often called "not A"). So the theorem can be restated as

More generally, where { A i} forms a partition of the event space,

for any A i in the partition.

See also the law of total probability.

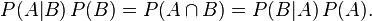

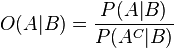

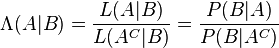

[ edit] Bayes' theorem in terms of odds and likelihood ratio

Bayes' theorem can also be written neatly in terms of a likelihood ratio Λ and odds O as

where

are the

odds of

A given

B,

are the

odds of

A given

B,

and

are the odds of

A by itself,

are the odds of

A by itself,

while

is the likelihood ratio.

is the likelihood ratio.

[ edit] Bayes' theorem for probability densities

There is also a version of Bayes' theorem for continuous distributions. It is somewhat harder to derive, since probability densities, strictly speaking, are not probabilities, so Bayes' theorem has to be established by a limit process; see Papoulis (citation below), Section 7.3 for an elementary derivation. Bayes's theorem for probability densities is formally similar to the theorem for probabilities:

There is an analogous statement of the law of total probability, which is used in the denomenator:

As in the discrete case, the terms have standard names.

-

is the joint distribution of

X and

Y,

is the joint distribution of

X and

Y,

-

is the posterior distribution of

X given

Y=

y,

is the posterior distribution of

X given

Y=

y,

-

is (as a function of

x) the likelihood function of

X given

Y=

y,

is (as a function of

x) the likelihood function of

X given

Y=

y,

and

and

are the marginal distributions of

X and

Y respectively, with

being the prior distribution of

X.

being the prior distribution of

X.

[ edit] Abstract Bayes' theorem

Given two

absolutely continuous probability measures

P˜

Q on the

probability space

and a sigma-algebra

and a sigma-algebra

, the abstract Bayes theorem for a

, the abstract Bayes theorem for a

-measurable random variable

X becomes

-measurable random variable

X becomes

-

![E_P[X|\mathcal{G}] = \frac{E_Q[\frac{dP}{dQ} X |\mathcal{G}]}{E_Q[\frac{dP}{dQ}|\mathcal{G}]}](http://upload.wikimedia.org/math/b/c/b/bcb58d4f262347072d35dea4a65977dd.png) .

.

This formulation is used in Kalman filtering to find Zakai equations. It is also used in financial mathematics for change of numeraire techniques.

[ edit] Extensions of Bayes' theorem

Theorems analogous to Bayes' theorem hold in problems with more than two variables. For example:

This can be derived in a few steps from Bayes' theorem and the definition of conditional probability:

Similarly, we have

which can be regarded as a conditional Bayes' Theorem, and can be derived by as follows:

A general strategy is to work with a decomposition of the joint probability, and to marginalize (integrate) over the variables that are not of interest. Depending on the form of the decomposition, it may be possible to prove that some integrals must be 1, and thus they fall out of the decomposition; exploiting this property can reduce the computations very substantially. A Bayesian network, for example, specifies a factorization of a joint distribution of several variables in which the conditional probability of any one variable given the remaining ones takes a particularly simple form (see Markov blanket).

[newpage]

Examples

[ edit] Example #1: Conditional probabilities

Suppose there are two bowls full of cookies. Bowl #1 has 10 chocolate chip cookies and 30 plain cookies, while bowl #2 has 20 of each. Fred picks a bowl at random, and then picks a cookie at random. We may assume there is no reason to believe Fred treats one bowl differently from another, likewise for the cookies. The cookie turns out to be a plain one. How probable is it that Fred picked it out of bowl #1?

Intuitively, this should be greater than half since bowl #1 contains the same number of cookies as bowl #2, yet it has more plain.

We can clarify the situation by rephrasing the question to "what’s the probability that Fred picked bowl #1, given that he has a plain cookie?” The event A is that Fred picked bowl #1, and the event B is that Fred picked a plain cookie. To compute P( A| B), we first need to know:

- P( A), or the probability that Fred picked bowl #1 regardless of any other information. Since Fred is treating both bowls equally, it is 0.5.

- P( B), or the probability of getting a plain cookie regardless of any other information. Since there are 80 total cookies, and 50 of them are plain, the probability of selecting a plain cookie is 50/80 = 0.625.

- P( B|A), or the probability of getting a plain cookie given Fred picked bowl #1. Since there are 40 cookies in bowl #1 and 30 of them are plain, the probability is 30/40 = 0.75.

Given all this information, we can compute the probability of Fred having selected bowl #1 given that he got a plain cookie by substitution:

As we expected, it is more than half.

[ edit] Tables of occurrences and relative frequencies

It is often helpful when calculating conditional probabilities to create a simple table containing the number of occurrences of each outcome, or the relative frequencies of each outcome, for each of the independent variables. The tables below illustrate the use of this method for the cookies.

|

Number of cookies in each bowl by type of cookie |

Relative frequency of cookies in each bowl by type of cookie |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

The table on the right is derived from the table on the left by dividing each entry by the total number of cookies under consideration, i.e. dividing each number by 80.

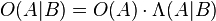

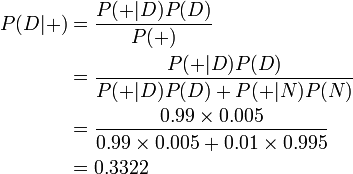

[ edit] Example #2: Drug testing

Bayes' theorem is useful in evaluating the result of drug tests. Suppose a certain drug test is 99% sensitive and 99% specific, that is, the test will correctly identify a drug user as testing positive 99% of the time, and will correctly identify a non-user as testing negative 99% of the time. This would seem to be a relatively accurate test, but Bayes' theorem will reveal a potential flaw. Let's assume a corporation decides to test its employees for opium use, and 0.5% of the employees use the drug. We want to know the probability that, given a positive drug test, an employee is actually a drug user. Let "D" be the event of being a drug user and "N" indicate being a non-user. Let "+" be the event of a positive drug test. We need to know the following:

- P( D), or the probability that the employee is a drug user, regardless of any other information. This is 0.005, since 0.5% of the employees are drug users. This is the prior probability of D.

- P( N), or the probability that the employee is not a drug user. This is 1 − P( D), or 0.995.

- P(+| D), or the probability that the test is positive, given that the employee is a drug user. This is 0.99, since the test is 99% accurate.

- P(+| N), or the probability that the test is positive, given that the employee is not a drug user. This is 0.01, since the test will produce a false positive for 1% of non-users.

- P(+), or the probability of a positive test event, regardless of other information. This is 0.0149 or 1.49%, which is found by adding the probability that the test will produce a true positive result in the event of drug use (= 99% x 0.5% = 0.495%) plus the probability that the test will produce a false positive in the event of non-drug use (= 1% x 99.5% = 0.995%). This is the prior probability of +.

Given this information, we can compute the posterior probability P( D|+) of an employee who tested positive actually being a drug user:

Despite the high accuracy of the test, the probability that an employee who tested positive actually did use drugs is only about 33%, so it is actually more likely that the employee is not a drug user. The rarer the condition for which we are testing, the greater the percentage of positive tests that will be false positives.

[ edit] Example #3: Bayesian inference

Applications of Bayes' theorem often assume the philosophy underlying Bayesian probability that uncertainty and degrees of belief can be measured as probabilities. One such example follows. For additional worked out examples, including simpler examples, please see the article on the examples of Bayesian inference.

We describe the marginal probability distribution of a variable A as the prior probability distribution or simply the 'prior'. The conditional distribution of A given the "data" B is the posterior probability distribution or just the 'posterior'.

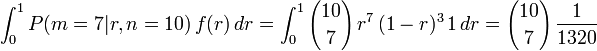

Suppose we wish to know about the proportion r of voters in a large population who will vote "yes" in a referendum. Let n be the number of voters in a random sample (chosen with replacement, so that we have statistical independence) and let m be the number of voters in that random sample who will vote "yes". Suppose that we observe n = 10 voters and m = 7 say they will vote yes. From Bayes' theorem we can calculate the probability distribution function for r using

From this we see that from the prior probability density function f( r) and the likelihood function L( r) = f( m = 7| r, n = 10), we can compute the posterior probability density function f( r| n = 10, m = 7).

The prior probability density function f( r) summarizes what we know about the distribution of r in the absence of any observation. We provisionally assume in this case that the prior distribution of r is uniform over the interval [0, 1]. That is, f( r) = 1. If some additional background information is found, we should modify the prior accordingly. However before we have any observations, all outcomes are equally likely.

Under the assumption of random sampling, choosing voters is just like choosing balls from an urn. The likelihood function L( r) = P( m = 7| r, n = 10,) for such a problem is just the probability of 7 successes in 10 trials for a binomial distribution.

As with the prior, the likelihood is open to revision -- more complex assumptions will yield more complex likelihood functions. Maintaining the current assumptions, we compute the normalizing factor,

and the posterior distribution for r is then

for r between 0 and 1, inclusive.

One may be interested in the probability that more than half the voters will vote "yes". The prior probability that more than half the voters will vote "yes" is 1/2, by the symmetry of the uniform distribution. In comparison, the posterior probability that more than half the voters will vote "yes", i.e., the conditional probability given the outcome of the opinion poll – that seven of the 10 voters questioned will vote "yes" – is

which is about an "89% chance".

[ edit] Example #4: The Monty Hall problem

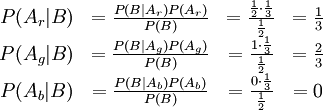

We are presented with three doors - red, green, and blue - one of which has a prize. We choose the red door, which is not opened until the presenter performs an action. The presenter who knows what door the prize is behind, and who must open a door, but is not permitted to open the door we have picked or the door with the prize, opens the blue door and reveals that there is no prize behind it and subsequently asks if we wish to change our mind about our initial selection of red. What is the probability that the prize is behind each of the green and red doors?

Let us call the situation that the prize is behind a given door A r, A g, and A b.

To start with,

, and to make things simpler we shall assume that we have already picked the red door.

, and to make things simpler we shall assume that we have already picked the red door.

Let us call B "the presenter opens the blue door". Without any prior knowledge, we would assign this a probability of 50%.

- In the situation where the prize is behind the red door, the host is free to pick between the green or the blue door at random. Thus, P( B | A r) = 1 / 2

- In the situation where the prize is behind the green door, the host must pick the blue door. Thus, P( B | A g) = 1

- In the situation where the prize is behind the blue door, the host must pick the green door. Thus, P( B | A b) = 0

Thus,

Note how this depends on the value of P(B).

[ edit] Historical remarks

An investigation by a statistics professor (Stigler 1983) suggests that Bayes' theorem was discovered by Nicholas Saunderson some time before Bayes.

Bayes' theorem is named after the Reverend Thomas Bayes ( 1702– 1761), who studied how to compute a distribution for the parameter of a binomial distribution (to use modern terminology). His friend, Richard Price, edited and presented the work in 1763, after Bayes' death, as An Essay towards solving a Problem in the Doctrine of Chances. Pierre-Simon Laplace replicated and extended these results in an essay of 1774, apparently unaware of Bayes' work.

One of Bayes' results (Proposition 5) gives a simple description of conditional probability, and shows that it can be expressed independently of the order in which things occur:

- If there be two subsequent events, the probability of the second b/N and the probability of both together P/N, and it being first discovered that the second event has also happened, from hence I guess that the first event has also happened, the probability I am right [i.e., the conditional probability of the first event being true given that the second has also happened] is P/b.

Note that the expression says nothing about the order in which the events occurred; it measures correlation, not causation. His preliminary results, in particular Propositions 3, 4, and 5, imply the result now called Bayes' Theorem (as described above), but it does not appear that Bayes himself emphasized or focused on that result.

Bayes' main result (Proposition 9 in the essay) is the following: assuming a uniform distribution for the prior distribution of the binomial parameter p, the probability that p is between two values a and b is

where m is the number of observed successes and n the number of observed failures.

What is "Bayesian" about Proposition 9 is that Bayes presented it as a probability for the parameter p. So, one can compute probability for an experimental outcome, but also for the parameter which governs it, and the same algebra is used to make inferences of either kind.

Bayes states his question in a way that might make the idea of assigning a probability distribution to a parameter palatable to a frequentist. He supposes that a billiard ball is thrown at random onto a billiard table, and that the probabilities p and q are the probabilities that subsequent billiard balls will fall above or below the first ball.

Stephen Fienberg [ [1]] describes the evolution of the field from "inverse probability" at the time of Bayes and Laplace, and even of Harold Jeffreys (1939) to "Bayesian" in the 1950's. The irony is that this label was introduced by R.A. Fisher in a derogatory sense. So, historically, Bayes was not a "Bayesian". It is actually unclear whether or not he was a Bayesian in the modern sense of the term, i.e. whether or not he was interested in inference or merely in probability: the 1763 essay is more of a probability paper.